Quitting

Some Jobs I've Left in NYC

The night I moved to Brooklyn I sat with my new roommate, Natalie, and searched for jobs. We didn’t have a table, or chairs, or wifi, so we sat on the floor with our laptops on upside down cardboard boxes. We used hotspots to scroll Indeed and CulinaryAgents.com. I applied to anything that would take less than 10 minutes. I sent out 150 applications within 24 hours.

I wanted a shitty job— a corner boutique that makes three sales a day— waiter at a restaurant ran by the mob— barista at a cafe that’s mostly around to be aesthetically pleasing. No attachment, no business casual, just 15 dollars an hour plus tips.

Only one place got back to me within the first week: the Anthropology at Rockefeller Center as a “sales associate.” Natalie and I spent an hour discussing which earrings I should wear (what looked the most like it would be sold in Anthropology), I put on my interview outfit (button up shirt under a black sweater over a pair of black dickies) (the sweater mostly covered the dickies patch… but not entirely), and went into the city.

I killed the interview. The manager fawned over me, finishing by saying, “I’m excited to see you again soon!” I bounced out of the store, high on validation. I bought a sandwich and sat outside 30 Rock to see if any SNL cast members would walk by. The Christmas tree was already up, and the sidewalks were clogged with tourists standing in each other’s way, hitting each other with their Tiffany and Prada shopping bags. As I chewed my deli turkey, I thought about being a sales associate for these people. Then I went into the Anthropology portal on my phone and rescinded my application.

The following week I went to five open calls at restaurants. I straightened my hair, took out my facial piercings, and sat in lower Manhattan restaurants during their lull between lunch and dinner. I filled out forms by hand with dried out pens, putting down all the information I knew they already had from my online application. I’d make small talk with the other young people who had little holes in their nostrils. All of them, and I mean all of them, were aspiring actors.

One restaurant was still open to the public, and a woman sat at the bar with a plate of spaghetti She silently watched us talking about small Brooklyn theater companies and their various reimagining of Shakespeare while prodding at (but not eating) her pasta. This went on for almost two hours, until the hostess came to tell us that the manager wouldn’t be seeing anyone else that day. The woman took a long sip from her martini as she watched us file back onto the streets, defeated.

I was finally hired by an Italian place in the East Village that specialized in brunch. I hadn’t brought my passport with me to onboarding, which was apparently essential before they could even think about training me. I desperately called Natalie and she, like an angel, raced up from Brooklyn to deliver it to me at Union Square.

The uniform was pink and white striped t-shirts, but they were completely out. I was given a stiff white long sleeve canvas shirt to hold me over until more came in. It was the same shirts the kitchen staff wore. When I asked what my official position was the manager said “oh, a little bit of everything.”

A very hungover gay guy named Jake walked me through everything, which was mostly warning me which coworkers to avoid. When I asked who not to avoid, he couldn’t think of anyone.The chefs looked me all the way up and down as I walked through the kitchen, which I had to do often. All the food was frozen. New coworkers did not introduce themselves or ask my name, but they did give me tasks without explaining how to do them. They would then return, five minutes later, irritated that I hadn’t figured it out on my own yet.

“The customers are, well, you know,” Jake said at the end of the shift. “Most of them are just regular annoying. The only guy who really sucks is Richard— he’s like 70, he comes in here every day. You’ll meet him. He mostly just harassed this girl, Julia, following her after her shifts and stuff. He left everyone else alone. She quit last week.”

He studied me for a moment, then added, “You kinda look like her, actually. He’ll like you.”

I did not meet Richard. The next morning I woke up with such a petrifying dread of going back that I called out sick. I called out of my next shift too, and my next one. I knew I didn’t want to go back, but quitting meant really giving it up, giving up my first New York opportunity. I told myself I was being dramatic and the job was fine, but still couldn’t get myself to go back to the East Village. After a week of this, Natalie put her foot down. She pretended to be me and quit over the phone, talking to my boss with the casual easiness of catching up with a friend. I lay at her feet shaking with anxiety.

My next job was a cafe next to a major New York City Museum, which I referred to as The Museum Cafe. The woman who hired me was my age and, hands in the pockets of her Carhartt hoodie the whole interview. I liked her a lot and almost never saw her again after getting hired.

The cafe was new, and attached to a fine dining restaurant that mostly hosted members of the museum board. No one involved seemed to know anything about coffee, and the cafe became more of an afterthought. The shifts were slow, and I spent most of my time sitting on a crate with a book. We got shift meals from the restaurant, which was usually extremely buttery, cheesy pastas from Chef Joe. Our general manager, Rachel, spent most of her time complaining about the servers in the restaurant, and was extremely hands off. I’d found the perfect shitty job.

But a few weeks in all hell broke loose. Three of the five baristas left in the same week. Rachel quit the night before Thanksgiving. The next day, a chef got a text from Rachel’s sister— Rachel had committed suicide. There was 48 hours of scrambling, of being shell shocked at work, of trying to coordinate a grief counselor, before a server noticed that Rachel’s instagram page was still watching the restaurant’s instagram stories. Finally someone got in contact with Rachel’s family directly, and learned that she was very alive, and had just fled upstate. It was a very poorly planned attempt at Gone Girl-ing.

In the aftermath, other managers from the restaurant group came in to do damage control. One approached me and asked who had been at the cafe the longest, and knew the most about coffee. I answered honestly that it was probably me— he offered me a “supervisor” position on the spot. There were no clear parameters of what the promotion would entail, but there was a guaranteed pay raise. I obviously accepted.

After a couple weeks of chaos and working double shifts, a new manager was hired. His named was Benjamin, and he always wore cologne and pants that were too tight. He very carefully groomed himself, including a thick mustache that earned him the nickname “Mario” from the kitchen staff. One day he walked around the restaurant and cafe asking every employee if they had any hairspray he could use. No one did. He never said hello or goodbye to anyone, and he always spoke between tight, clenched teeth as if he was holding himself back from yelling. He did not let employees sit on crates and read all shift.

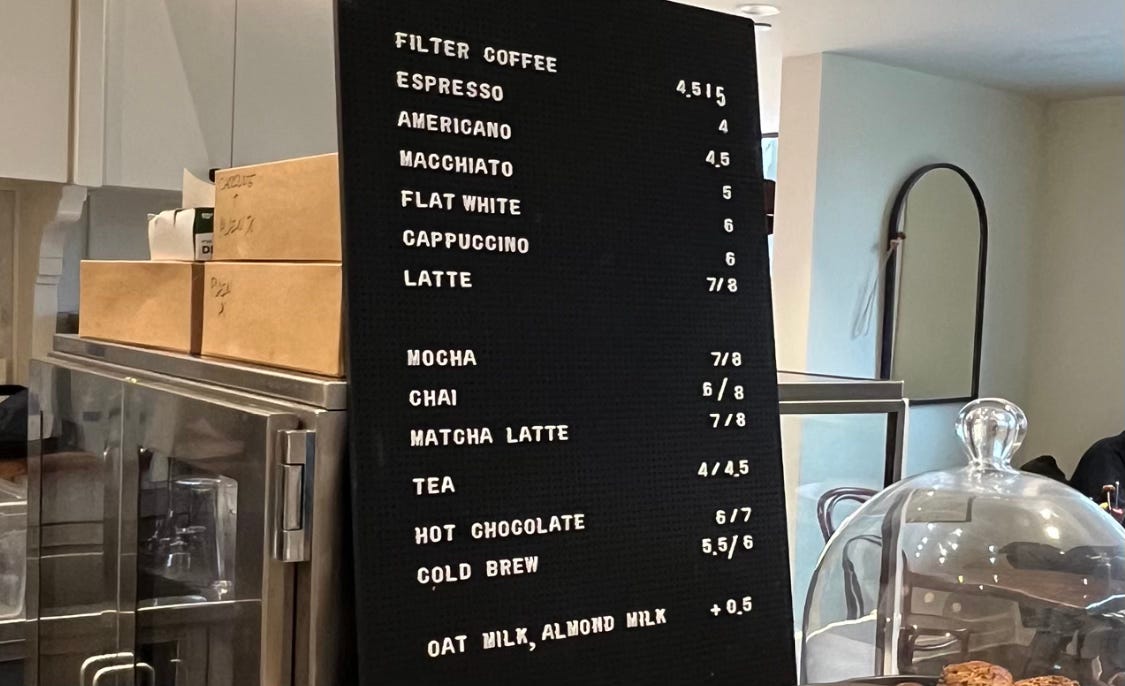

Two types of people came into the museum cafe: The first were locals over the age of 60. They did not say “please” or “thank you” but still expected “you’re welcome”. They gawked at the prices of the coffee every time, even if they came in every day. They trailed off in the middle of their orders, and needed a question repeated multiple times to get through their hearing aids. They asked, “don’t they pay you enough?” when the tip screen came up on the iPad.

The second were European tourists. They came in with their children who were cranky and exhausted from a day at a museum they clearly hadn’t wanted to go to. They got genuinely angry with me that I didn’t speak French. They told me that if I gave an Italian our espresso, I’d get slapped in the face. They hit “no tip” like it was a natural instinct. If they ever mistakenly did leave a tip, they would ask me to refund the whole transaction so they could do it again, and leave none.

There were still good things— I got three of my friends hired. For a couple months, I consistently had a buddy while I worked. We were bad employees. We gossiped, and went on our phones, and made plans in front of customers. I organized boxes in the storage room and balanced the drawer once a week for my supervisor pay. I trained a dozen people, repeating again and again how to make a cappuccino. Very few of them ever figured it out, but our customers rarely actually knew what they were ordering.

People came and went quickly, a couple of weeks to a couple of months. By February there was only one other original hire, an Eastern European woman named Ana. She was at least ten years older than everyone else there, and had the stamina of a workhorse. She’d been in the states for 8 years and was saving up money to open her own restaurant back home. Her other job, which she almost always went to straight from work, was a restaurant in Times Square. She never left without sneaking a glass of wine from the restaurant.

She loved to talk— about books, movies, politics, everything. She told me, with a grave serious in her voice, that I should never go on anti-depressants. If I ever came into work with the sniffles she would demand the chefs make me soup. She brought her own ginger tea into work, and would insist that I have some because it was good for my liver. She remembered the name of everyone who worked in the museum (our only regulars) and would argue with them over current events. She flirted relentlessly. She would not hesitate to tell someone she thought was rude to never come back. She would curse out management every time they did something she disapproved of. Once, when I said I was low on cash, she told me I should just offer someone a green card marriage.

“People pay thirty, fourty-thousand dollars for those,” She said. “That’s what I did— but the bastard I gave the money to abandoned me.”

She told me, when she went back to Europe, I would have to come to her apartment and take all of her books. “I won’t be able to bring them all back with me,” She said. “And I need them to go to someone I trust.”

Everything in restaurant was a pale cream color, which was trying to look sleek and modern, but actually just revealed how grimy every surface was. The floors were especially bad. They were wood covered in a patchy, uneven lacquer. They always looked dirty, no matter how much mopping we did. When Benjamin scheduled getting the floors redone, he buzzed with excitement about it for weeks. Every time he came into the cafe he’d ask, “Aren’t you excited to get rid of this ugly floor?”

The process took days, and taking off the old lacquer covered the entire cafe in a thick coat of dust. We spent hours cleaning, and my allergies were set off long after we’d cloroxed everything. When the floors were finally finished, they looked exactly the same as before. Benjamin refused to acknowledge them.

A security guard from the museum asked my coworker for her number, then came back to yell at her when she never replied to his texts. A boy had a seizure his first shift, and was lucky enough that the person training him was in school to be an EMT. He lay him down and held his head until the ambulance came. There was, of course, work crushes and dramas. Two baristas took the same week off, and both came back with dark tans each saying that they had gone to Jamaica. I didn’t press, but Ana did— she then insisted she get an invite to their wedding.

We were always out of a milk, or a syrup, or even coffee beans. Whenever I tried to tell someone we needed more, they’d say I should ask someone else. The chef, or the kitchen manager, or the hostess, even. A different person seemed to be handling cafe orders every day— and it was never actually anyone in the cafe.

Customers always asked for recommendations in the area. “If I could afford to spend any time in this neighborhood, I would’t work here,” I joked to them. They were never amused.

We let dogs come inside and offered them treats, despite it being against health code. One day, a woman came in with two dogs and immediately let go of their leashes. Both dogs bee-lined behind the counter. The woman did not try to stop them as they started jumping on me.

“They really shouldn’t be behind the counter,” I said.

“Oh, it’s fine,” She said, as if I was worried about the dogs’ personal comfort behind the counter.

“I’m just allergic,” I said, as one licked my arm.

“They just want treats,” She said.

I gave each of them treat. One swallowed, and then immediately started hacking it back up onto the floor. I looked at the woman.

Instead of doing anything about the dog she said, “I’ll do an almond latte.”

A server at the restaurant quit, and Benjamin said it was because he was a male escort. He did not say this to me— Benjamin only ever chatted with the boys. He said it to my friend who, obviously, asked how Benjamin would know that. Benjamin didn’t have an answer.

Benjamin’s bias towards men was so strong that, eventually, the last girl who worked there texted the group chat begging him to hire a woman. “I’m all alone here :,(“ She said. “I will,” He replied. (He never did.)

By April I was ready to leave. My “supervisor” pay (that I was still getting even though I did very little supervising) wasn’t quite making up for the people I dealt with every day. Then the good people started leaving. All of my friends got better gigs. Ana found another restaurant to sponsor her visa. But the final nail in the coffin was when Chef Joe left, and his family meals left with him. The first shift without one of his beautiful, buttery pastas, I spent most of my time drafting a resignation text. That night I was back in my apartment, lying in Natalie’s bed, searching for my next job to quit.